Posts published on January 21, 2016

Colleges Revamp General Education Requirements

But for all the talk about moving past distribution requirements, it turns out that they are alive and well, but with twists that deal with some of the criticisms.

That is one of the key findings of a survey — released today by the Association of American Colleges and Universities — of its members on issues such as general education, learning outcomes and teaching approaches. The results being released today are the second from a survey completed by provosts or chief academic officers at 325 AAC&U member colleges and universities.

Other key findings relate to a growing majority of colleges having intended learning goals or outcomes for all students, and some skepticism about whether faculty members are using technology in the most effective ways.

Distribution Requirements

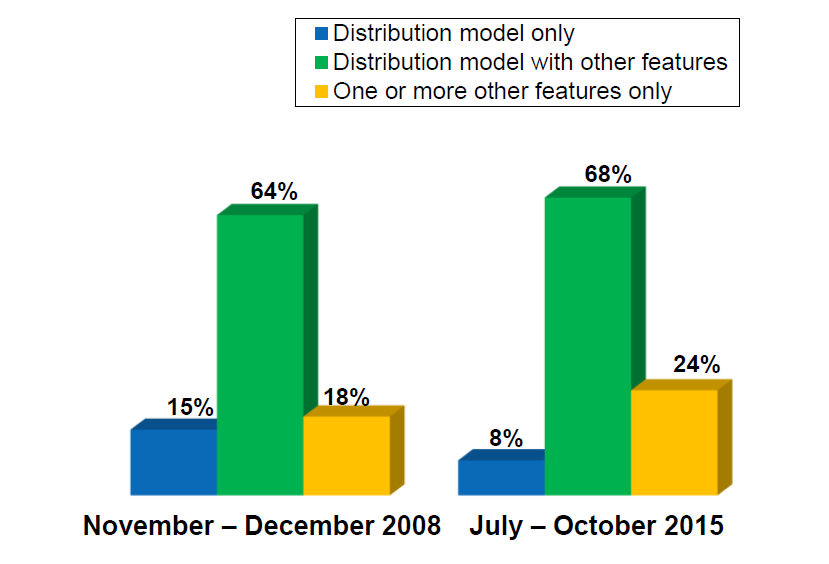

Many general education programs have been built around distribution requirements. And the AAC&U survey suggests that relatively few institutions have abandoned them. In the 2015 survey, 76 percent of colleges reported using distribution requirements, down only modestly from the 79 percent of colleges that reported using distribution requirements in a 2008 survey. But the norm — even more now than in 2008 — is a distribution requirement plus other features for general education. In fact, the share of colleges relying only on distribution requirements fell nearly in half between the two surveys.

According to the AAC&U report, colleges are building on distribution requirements by also requiring common intellectual experiences of students, thematic courses, learning communities (in which groups of students take a common sequence of courses) and other techniques.

In the survey, academic leaders were asked to indicate the design elements of their general education programs — and they could list more than one such element.

Design Elements of General Education, 2015 Survey

| Element | Percentage of Colleges |

| Distribution model | 76% |

| Capstone or culminating studies (in majors) | 60% |

| Upper-level general ed requirements | 46% |

| Core curriculum | 44% |

| Thematic required courses | 42% |

| Common intellectual experience | 41% |

| Capstone experience (in general ed) | 26% |

| Learning communities | 22% |

The University of Nevada at Las Vegas is an example of a university keeping distribution requirements but also adding other approaches to general education. So undergraduates across fields are still required to complete courses in writing, mathematics, fine arts and humanities, social sciences, and life/physical sciences, among other categories. But UNLV has added other required elements, such as a first-year seminar, a second-year seminar and new upper-division requirements in majors, leading to a “culminating experience.”

Chris Heavey, vice provost for undergraduate education at UNLV, said the university was trying to more closely link its general education requirements to the major and to institutional learning goals. But he said it was “very challenging for most institutions to go entirely away from distribution models because the structure and resources of the institution [have] probably grown up to support those offerings.”

Debra Humphreys, senior vice president for academic planning and public engagement at AAC&U, said that “many people theoretically get that it’s not adequate” to just create categories of courses for students, and to require them to take some number of courses in each category. But she agreed with Heavey that “institutions are still organized largely by disciplinary categories that correspond to knowledge areas.” As a result, colleges “continue to chip away” at reliance on distribution requirements “but we’re still not quite there yet” in terms of moving to an entirely new model.

Humphreys is encouraged by moves like that of UNLV’s, which use distribution as a base for general education but don’t leave it there. She also said it was important that general education requirements be linked to desired learning outcomes, as the survey suggests colleges are doing.

On learning outcomes, the survey found that 85 percent of colleges report that they have a common set of desired outcomes for all undergraduates, regardless of major. That figure is up from 78 percent in the 2008 survey.

Further, of those institutions that have a common set of learning outcomes for all students, there is consensus about some of the elements that are included. The table below shows, from the 2008 survey and the 2015 survey, the share of colleges reporting that these skills and knowledge areas are part of their learning outcomes.

Common Elements of Colleges’ Learning Outcomes

| Skills/Knowledge | 2008 | 2015 |

| Writing skills | 99% | 99% |

| Critical thinking and analytic reasoning skills | 95% | 98% |

| Quantitative reasoning skills | 91% | 94% |

| Knowledge of science | 91% | 92% |

| Knowledge of mathematics | 87% | 92% |

| Knowledge of humanities | 92% | 92% |

| Knowledge of global world cultures | 87% | 89% |

| Knowledge of social sciences | 90% | 89% |

| Knowledge of the arts | n/a | 85% |

| Oral communication skills | 88% | 82% |

| Intercultural skills and abilities | 79% | 79% |

| Information literacy skills | 76% | 76% |

| Research skills and projects | 65% | 75% |

| Ethical reasoning | 75% | 75% |

| Knowledge of diversity in the United States | 73% | 73% |

| Integration of learning across disciplines | 63% | 68% |

| Application of learning beyond the classroom | 66% | 65% |

| Civic engagement and competence | 68% | 63% |

| Knowledge of technology | 61% | 49% |

| Knowledge of languages other than English | 42% | 48% |

| Knowledge of American history | 49% | 47% |

| Knowledge of sustainability | 24% | 27% |

Humphreys said she was pleased by one of the topics that saw the biggest increase from 2008 to now: research skills and projects. She said this was consistent with the idea of working in teams and working to solve problems — skills that employers seek and that promote cohesive learning that goes beyond one course or discipline.

Some of the scores on the list may be hard to explain. For example, the results suggest more colleges include study of a language other than English as a learning outcome. But a report from the Modern Language Association a year ago found foreign language enrollments declining, and many foreign language departments in the last few years have found themselves the target of cuts.

The high percentage (85 percent) of colleges reporting that knowledge of the arts is a learning outcome is also at odds with the relatively few colleges that require arts study for all students. Humphreys said she suspected that the high figure was due to provosts looking at requirements for arts and humanities courses and counting them as arts requirements.

Are Students Aware?

The provosts were also asked whether they believed students were aware of the desired learning outcomes at their institutions. Only 9 percent said that they believed all students understood the desired learning outcomes, and only 36 percent said that a majority of students understood them.

Humphreys said that academics should be “very worried” about these findings. She said she worried that faculty members may spend lots of time developing a general education program consistent with their institutions’ missions, launch the system with fanfare and then not do enough to promote understanding of it. That may mean that, a few years after a program launch, students may not know much about it.

The findings also point to a need for more of a focus on academic advising and for advisers to talk to students about the broad goals of general education, and not just requirements to be finished.

The completion agenda, she said, may make this more difficult. Many advisers are “under pressure to get students through as soon as possible,” she said. That is admirable, but means that students aren’t necessarily being asked about how course plans “relate to learning broadly,” but rather are encouraged to find “an efficient way to get this done.”