Posts published in April, 2016

Decreasing Expenses for College Students

BY DAVID GUTIERREZ

Being a college student is tough, especially from the financial standpoint. Even if you forget student loans that weigh down many people for years after, merely maintaining a decent lifestyle during college is hard when you cannot have a full-time job. Here are a few tips on how you can decrease your living expenses without sacrificing too much.

1. Budget Carefully

If you’ve never had to budget your money before, it is going to be hard. But you have to learn this art if you want your student loan to last long enough to get you to the end of your education. Make sure your spending is only limited to things you really need. Avoid impulse purchases. Have a certain limit on your spending and do your best not to exceed it. Get a personal finance app to make organizing your funds easier.

2. Buy a Used Car

A freshly manufactured car immediately loses about forty percent of its price after being sold the first time, which means that if you know your way around, you can get some pretty extreme bargains. However, buying used cars is an art in and of itself, and it is just easy to buy a piece of scrap that will fall apart the first time you sit behind the wheel. So, if you want to avoid nasty surprises, it pays to look through a few specialized resources prior to committing to anything.

3. Make Use of Student Discounts

Students get an enormous number of discounts on all things imaginable, from clothes and food to cinema and concert tickets. You could easily get an Amazon promo code online before you buy for instance. However, it doesn’t mean you should go on a spending spree just to enjoy your discounts while they last – on the contrary, they should serve as a topping to other wise spending habits. Only buy things you are really going to use, and look for retailers that make special offers for students.

4. Be Ready to Get Rid of Unnecessary Things

Many things can catch a top dollar on eBay, and used textbooks can be exchanged for a gift card at Amazon. Whenever you feel that a thing is just sitting around eighty percent of the time and you are unlikely to use it ever again, try to sell it to somebody who needs it more than you. It will simultaneously help you to raise some money and get rid of unnecessary stuff that does nothing but distract your from really important things.

5. Avoid Fast Food and Eating Out

Constant visits to McDonald’s and donut shops may not seem like a costly affair, but they do add up – not only to your waistline, but to your expenses as well. Cooking your own food is healthier, less expensive and much less time-consuming than trying to get rid of all these extra calories later on. Or, if you really hate cooking, use a college meal plan.

Cutting your expenses is much easier than it may seem. Human’s ability to invent new things to waste money on is unlimited – but it also means that you can safely eliminate more than half of your current

David Gutierrez has worked in the field of web design since 2005. Right now he started learning Java in order to get second occupation. His professional interests defined major topics of his articles. David writes about new web design software, recently discovered professional tricks and also monitors the latest updates of the web development

Report: Last affordable options for college students are fast disappearing

by MIKHAIL ZINSH

The converging trends of falling state investment, rising tuition and stagnant incomes have finally pushed higher education out of the grasp of low- and middle-income Americans, even at community colleges, a new report contends.

The Topic: College affordability

Why It Matters: As policymakers try to increase college-going, the cost has finally exceeded the grasp of low- and middle-income Americans

College is less affordable now, when adjusted for inflation, than it was before the economic downturn, student financial aid no longer is enough to fill the gap, and low- and middle-income families already are having trouble making ends meet just to cover living expenses, the report said.

Related: The rich-poor divide on America’s college campuses is getting wider, fast

“If you’re making $10,000 to $30,000 a year, and you need 10 percent to 15 percent of family income to attend community college, it’s just not going to happen,” said Joni Finney, director of the Institute for Research on Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania and coauthor of the study.

The cost of living in general and of college in particular has increased for many low- and middle-income families while wages have largely stagnated over the past few decades, and per-student state investment in public education continues to lag pre-recession levels, the report said.

Even at community colleges, most full-time, low-income students would need to work more than 20 hours a week to afford their educations—a workload experts say makes it all but impossible for them to successfully complete a degree.

Related: Colleges that pledged to help poor families have been doing the opposite, new figures show

The result is that far fewer low- and middle-income students will enroll in college at a time when the country has set a goal of producing more degree-holders to stay competitive with international economic rivals.

While policy leaders “talk passionately about wanting to level the playing field,” their funding commitments haven’t aligned with the goal of helping needy students, the study said. “Unless we make college affordable for people of all financial means, opportunity through higher education will be a false promise.”

Unlike other attempts to analyze college affordability, the report—a joint effort of the Higher Education Policy Institute, Vanderbilt University and the University of Pennsylvania—examined tuition and cost-of-living expenses, and compared those to the typical state and federal aid given to students who aren’t well off.

Click here to enlarge

Between 2008 and 2013, the last period for which the information is available, 15 states lowered the full-time cost of attending community college. Four-year public universities became more affordable in six states.

But affordability across all types of colleges and universities declined in 45 states.

Related: States moving college scholarship money away from the poor, to the wealthy and middle class

Families of students at four-year public universities and colleges in high-population states including Illinois, New Jersey and Pennsylvania now pay the equivalent of 35 percent or more of their annual incomes to afford school. In Massachusetts and Virginia, the family of a typical student is charged the equivalent of 32 percent of its annual income.

Attending community colleges in many states accounts for around a fifth of students’ family incomes, on average.

Typical college expenses in 12 states are low enough so that community-college students could afford the cost of attendance by working 20 hours or less: Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia.

“Where you grow up can determine your opportunities for higher education,” the authors write. “College costs, available aid, and institutional options vary dramatically by state, sometimes within the same region.”

Related: Government data single out schools where low-income students fare worst

Low-income and middle-class families are feeling the financial squeeze even before contending with tuition.

Federal data show that annual expenses already exceed annual incomes of families earning less than $50,000. Even households earning between $50,000 and $69,000 spend an average of 87 percent of their wages on typical purchases, making it hard to save for college.

“This has been happening slowly, over time, since the early 1990s,” Finney said in an interview. “When the state abdicates responsibility for public policies related to affordability, it disproportionately hurts low- and middle-income families.”

How to fix this is another question, particularly as universities warn of even deeper financial problems.

“Absent any kind of state and federal policy interventions, these trends will only escalate,” Finney said.

And while some states, such as Tennessee and California, have worked to keep tuition low—especially for community college students—tuition consumes only a third of what students have to pay. Fees, books, supplies, food, and housing add substantially to that.

Meanwhile, higher-income families have come to enjoy increased proportions of states’ financial aid.

While the amount of need-based state financial aid for students at four-year public universities and colleges has barely budged between 1996 and 2012, state financial aid for high-income students at those institutions jumped 450 percent, the report said.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about higher education.

The Classroom of Tomorrow: 21st-Century Classroom Design

BY JANE HURST

Today, your classes may be set in a traditional classroom, with old-fashioned desks and maybe even a blackboard. But, that is about to come to an end. The future of classrooms is here, and it is only going to get better and better. Modern classrooms come complete with new design concepts, better accessibility, more mobility, and teachers are getting to know their students more so they can better help them to achieve greatness in their studies. Let’s take a look at how classrooms are changing for the better.

Zones

One of the biggest changes in classrooms is that they are now often divided into special zones. A practical classroom will have a zone for group gatherings, such as meetings, and the spaces will be a lot more flexible. Professors can get creative with spaces by setting up areas for students working alone, in pairs, and in groups. Today’s educators are coming to realize that comfort is important when learning, and many classrooms incorporate sofas, beanbag chairs, etc., which can be found at thrift stores for next to nothing. Furniture can be arranged to create nooks, where you will find bookshelves, study areas, etc.

Accessibility

There was a time when a student in a wheelchair couldn’t get into a classroom. Today’s classrooms are made with accessibility in mind. The classrooms are designed to ensure that all learners get the most out of their experience. If any of your students need better accessibility for any classes, don’t hesitate to ask them for feedback to find out exactly what they need. Then, you can come up with a way to accommodate them. Talk to the administration and ask to have bulletin boards, whiteboards, hooks, etc. lowered to accommodate everyone.

Mobility

Today’s student doesn’t necessarily sit in one spot for hours on end. Modern education is all about mobility, and thanks to the Internet, there is no end to how mobile one’s studies can be. Some students thrive in a traditional classroom environment, but there are many who do not. Set up classrooms in a way that students can get up and move around while still being able to take in everything going on in the class. There are many devices and apps that make this easier, and you can have them use blogging apps (WordPress and EduBlogs), math practice apps, and more, all from their mobile devices so they aren’t stuck in their chairs all day. You can even create educational blogs with your own special logo (with the help of free Shopify Logo Maker) and design.

Show Respect

At one time, it was expected that students showed their instructors respect, but reciprocation was never necessary. That has changed. Today, instructors need to be respectful of their students. Each one has different needs, and some do better in their studies than others. Rather than being disrespectful of those who have difficulties, get to know them better, and find out what it will take to help them make it to graduation. As they grow, you will find that you will be growing as well.

Inspiring Students

Rather than giving students assignments and expect them to be creative, find ways to inspire their creativity so it is always there, and they don’t have to turn it on and off. There are many ways that you can do this. You can create an inspiration zone that students can use at any time. Teach them the characteristics of creativity, from risk taking to learning how to deal with failure to keeping at it, and help them learn how to apply these characteristics to their own work.

Byline:

Jane Hurst has been working in education for over 5 years as a teacher. She loves sharing her knowledge with students, is fascinated about edtech and loves reading, a lot. Follow Jane on Twitter!

Thank you!

Promising Potentials of Virtual Reality in Higher Education

By Robert Parmer

While virtual reality has been around for decades, new visions for a virtual world are now becoming realistic. The term virtual reality was coined by Jaron Lanier in the 1980’s, although other terms for describing the concept such as “artificial reality,” and “virtual worlds” have existed previously.

Virtual reality involves a couple of main components: an immersive headset that blocks out the real world to an extent, and an interface such as a computer or smartphone. The view from within a VR headset is stereoscopic, meaning it features a left and right screen–one for each eye. Headsets are more affordable than ever, with quality VR gear already going for less than $100.

Odds are that virtual reality isn’t immediately what you think of in regards to higher education. However, it’s becoming more relevant than ever.

Online learning has certainly changed the scope of education in recent years, allowing students to partake in distance learning–a modern phenomenon. It’s now possible for people to work when and where they want to. But what if it were possible to learn in an immersive classroom environment, without ever having to actually step foot into a classroom?

Virtual Classrooms

Online learning has been viewed as a double-edged sword by many students, especially those who desire engaging, face-to-face contact with their professors. With the use of virtual reality, virtual classrooms are becoming increasingly more feasible for students. This means that the days of emailing a question to a profession and patiently awaiting a response are over.

Without leaving the comfort their bedrooms and pajamas, students will be able attend classes as an avatar: a slightly simulated version of themselves. What sets this apart from typical distance learning is that virtual classrooms aren’t limited by webcams. Students will be able to virtually raise their hands to ask questions, take part in more hands-on virtual experiments, and even walk around a simulated classroom if they choose.

3D Modeling

Most people are familiar with VR and its applications to video games, but it’s by no means limited to gaming applications. The fact stands: people’s interest have been truly sparked by virtual reality, and it’s becoming more and more popular. The industry is expected to be worth $30 billion by 2020.

Virtual reality will be extremely relevant to hands-on 3D models that could very well replace the cliche frog dissection experiment forever. This will save resources and will prove to be much less wasteful.

For example, envision a virtual woodworking shop. When learning the ropes of woodworking, there’s obviously going to be a lot of associated waste and danger. It’s a byproduct of error and coming to understand the detailed processes that make up the job. Imagine if while learning how to create beautifully crafted pieces of furniture, a carpenter could opt out of using real materials until they were well-versed in foundational techniques.

Now take that concept and adapt it to a medical student. Rather than working with cadavers and other expensive or difficult-to-access educational tools, simulated alternatives through VR will be much less wasteful and easier to attain.

Increased Gamification

A graphic by Knewton tilted The Gamification of Education defines gamification as “the use of game design elements in non-game contexts.”

It also points out that “Game players regularly exhibit persistence, attention to detail, and problem solving, all behaviors that ideally would be regularly demonstrated in school.”

While video games are considered by many to be a waste of time, new ways of engraining gamification into learning challenges the idea that all video games turn brains to mush. Gamification is the concept of using video games as an educational tool. It can be incentive-based, or simply introduce ideas that are being studied through video games.

This approach resonates well with many students. It creates an enjoyable, atmospheric learning environment. Learning through gaming feels less forced and more enjoyable to many students.

Simulated “Field Trips”

The distance that separates college students from visiting the most captivating places in the world is no longer a pitfall for students and their finances. Google Cardboard is a very inexpensive way for college students to experience VR for the first time. With a price tag of less than $20 and a design that is economic and simple to use, Google Cardboard turns any smartphone into a virtual reality interface.

Traveling is expensive, that much is certain. By using VR for virtual touring, simple smartphone rigs can be turned into immersive headsets that allow students to take part in advanced tours and intricate virtual trips. Imagine if an archeology students could take part in a virtual dig, or if someone studying wildlife conservation efforts was able to see affected areas without ever leaving their home.

The next few years are a pivotal timeframe for virtual reality, as it will continue to rapidly expand. This short amount of time will tell; as VR continues to integrate itself into our education and our everyday lives.

Robert Parmer is a freelance web writer and student of Boise State University. Outside of writing and reading adamantly he enjoys creating and recording music, caring for his pet cat, and commuting by bicycle whenever possible. Follow him on Twitter @robparmer

How Faculty Can Improve Final Exams

Fernanda Zamudio-Suaréz, Chronicle Of Higher Education

Many colleges are now gearing up for one of the most stressful times of the year. No, not March Madness, but final exams. Over the years, The Chronicle has published reams of advice on how to improve, conduct, and cope with this all-important moment in the academic calendar.

From abolishing finals to combating cheating, here are highlights from our most popular finals-themed advice columns as well as perspectives shared by seasoned instructors:

Final Exams or Epic Finales

Instead of having students scramble to finish a final exam and then bolt out the door, faculty members should end the semester with a memorable learning experience — an epic finale, Anthony Crider, an associate professor of physics at Elon University, wrote last year. Unlike a test, a “finale” can spark discussion and reflection afterward.

“This is exactly how a semester of learning should end,” Mr. Crider wrote. “Or, more to the point, this is how learning should not end.”

Mr. Crider detailed how he had scrapped his final for a day of applied research. Students did not have to write an accompanying essay, just apply what they had learned in the course. Here are some of his tips on handcrafting a finale:

Lower the stakes: Finales should account for about 10 percent or less of a student’s final grade, Mr. Crider said. That reduces pressure on both professors and students during an often experimental event.

Collaborate: Let students think aloud and work with one another, and listen in.

Shroud it in mystery: Intrigue students by not revealing the exam’s format.

Skeptical about the idea’s transferability? A teaching fellow in theology and religious studies at the Catholic University of America was inspired by Mr. Crider’s essay to stage a heresy trial, an ecumenical council, and a monastic chartering for an epic finale in his course on the early history of Christianity. Students were assigned to groups before the finale and prepared for the different historical situations.

“If I wanted academic content to come down to earth and apply to my students’ lives, playing games seemed the best way to do it,” Andrew Jacob Cuff wrote. “Maybe it’s time for you to give it a try, too.”

To Stop Exam Cheats, Try Assigning Seats

Want to stop suspected cheaters? Give students the ultimate plot twist before the final exam and assign their seats.

A study by economists found that when students’ seats were assigned on the day of a final exam, cheating was reduced drastically. The study also allowed researchers to conclude that at least a tenth of students had cheated on the midterm. The researchers observed 1.1 more shared incorrect answers when students could choose who they sat next to than when their seating was assigned.

With assigned seating and three more proctors, researchers found no signs of cheating in the final.

Facing the Dreaded End-of-Term Question

When one professor announced there would be no final exam, hands shot up to ask the obvious question: “Do we still have to come to class?”

While it’s easy to snap at students who ask about class attendance, wrote Raymond DiSanza, an assistant professor of English at Suffolk County Community College, in New York, faculty members should encourage students to want to come to class, not feel forced to.

Mr. DiSanza advised professors to turn their frustration to motivation: a challenge to get students so excited about the material that they want to show up.

“Or, maybe most important,” he wrote, “you can do everything in your power to bring joy back to the classroom, to remind your students that what goes on in the classroom is about more than just the classroom, regardless of discipline.”

How Exams Improve Students’ Access to Their Brains

Finals are a rite of passage for college students. And while exams may not be the best way for students to learn, they are still educationally valuable, said Henry L. Roediger III, a psychology professor at Washington University in St. Louis.

“I really worry about courses that don’t have them, to be honest,” he said. “More and more, faculty are not having exams. Well, that means their students are not reviewing the course material they taught them that semester.”

He added: “As long as you have an exam that asks deep, meaningful questions, questions that make people interrelate and integrate things across the course, they’re not just a measurement instrument, but they are a very important learning instrument.”

To the extent that information learned in a course is worth retaining, Mr. Roediger said, finals are worth the pain.

Stop Telling Students to Study for Exams

While studying for exams is a sign of academic responsibility, it’s also a form of instrumentalism, of achieving a goal, wrote David Jaffee, a sociology professor at the University of North Florida. Instead of urging students to study for an exam simply to pass a class, he said, professors should tell students to study for the sake of learning and understanding.

By repeating the phrase “study for exams” and administering such a test, he said, faculty members encourage the view that every academic action is a means to an end.

In the Land of Tests, the ‘Exam Dream’ Comes in Many Guises

Long after the blue books are handed in and final grades are posted, one thing still haunts current and former students — the exam dream.

Most such dreams follow the same mold: A nervous student arrives ill-prepared for an exam or to turn in a final paper, and panic ensues.

In a country plagued by tests, the dream is common. One scholar offered this explanation to The Chronicle’s Eric Hoover: Tests are many students’ first school experience, and those memories are natural early fears that manifest themselves years later, when threats are gone.

From college presidents to real-estate agents, many people experience the nightmare when the cramming is long past.

Fernanda Zamudio-Suaréz is a web writer. Follow her on Twitter @FernandaZamudio, or email her at fzamudiosuarez@chronicle.com.

How to Get Money Fast as a Student

BY MELISSA BURNS

We all sometimes get into situations when we need a certain (sometimes considerable) sum of money, and need it soon. Students, as people who usually don’t have a stable and dependable source of income and have to dedicate most of their time to studies, are especially prone to this.

So how does one get out of such a pinch? Are there legal ways of laying your hands on some cash when you have nowhere to borrow from and don’t have time to earn it? There certainly are, and we are going to tell about them.

1. Selling Things on eBay

Look around. We all have stuff that is just lying around collecting dust, not getting used. You may keep it for sentimental reasons or because you hope it will come in handy one of these days, but truth is, if you don’t use something for a year, there are nine chances out of ten that you aren’t going to use it ever. Selling such things on eBay will provide you with much-needed extra cash and free up your living space and your life for new things.

2. Getting a Loan

For students who are often already weighed down by considerable college debts, getting a loan may really sound like a bad idea. However, it is all a matter of perspective – if you have no alternatives, another couple of thousands added to your debt doesn’t matter much – and it can alleviate your current problems. The trick about installment loans is to find a loan company with reasonable conditions and go for it. There are many firms that are ready to give you a substantial loan even if you already have bad credit – if you take your time and look carefully, you are certain to find something.

3. Being an Extra

There are numerous ways to make extra money from TV – ways you either have no idea about, or simply never seriously considered. One of them is registering with a dependable extra agency and looking for casting ads. You don’t have to do virtually anything but to stay or walk around, and are paid extremely well (especially for this kind of job) – sometimes more than $100 for a single day.

4. Saving

Yes, saving money is very much akin to making them. Take a careful look at your lifestyle and ask yourself what things you can do without – if you are really thorough, you will find a lot of ways to decrease your current spending without sacrificing anything substantial. It may not be as flashy as many ‘get rich fast’ schemes, but at the end of the month, it can easily leave you with a humble but very appreciable additional sum of money.

If you really need money and if you stop limiting your imagination, you will be amazed how many ways of earning extra cash are just lying around, waiting to be used. Just don’t be shy, and you will certainly find ways to raise enough.

Melissa Burns graduated from the faculty of Journalism of Iowa State University in 2008. Nowadays she is an entrepreneur and independent journalist. Her sphere of interests includes startups, information technologies and how these ones may be implemented.

– See more at: https://collegepuzzle.stanford.edu/?p=5191#sthash.LFA7qbcy.dpuf

How to Study More Effectively

BY JANE HURST

Obviously, if you are going to college, you want to get great grades and move on to a wonderful career. But, getting those great grades is often a lot easier said than done. For some students, it comes very easily, and it seems like they never have to crack open a book to make straight A’s. For others, it is a constant struggle to maintain a C average. But, you don’t have to struggle to get the good grades you want. What you do need to do is find ways to study more effectively. Here are some suggestions.

- Prepare to Study– Before you can begin studying, you need to get yourself prepared. Keep a day planner, and write down everything you have to do, and study. This will help you to better schedule study times. Block out certain hours each week for studying, and try to study at the same time of day for each study session. Create a study agenda, so you have time to study each aspect of the subject matter.

- Get into the Right Mindset– No matter how much you need to study, if you aren’t in the mind set for it, you aren’t likely to retain a whole lot. You need to know how to properly approach studying, and when to approach it. For instance, you should strive to study when you are in a positive mindset, and you need to keep that positive mindset when you are studying. Try to avoid negative thinking, such as thinking that you are never going to have enough time to study for an exam.

- Practice, Practice, Practice– When it comes to studying, the more you practice what you are learning, the more you will remember. Be sure to outline and rewrite your notes. The more you do this, the more the material will be embedded into your brain. Use memory games to help you remember dates, locations, and other facts. Practice at every opportunity, both alone and with friends and classmates.

- Find a Place to Study– Whether you are staying close to home, or choose to study abroad Israel or another country, you need to find a good place to study. It may be that your dorm is too loud and busy for you to be able to concentrate. Take time to find a quiet place where you can feel relaxed and will be able to study effectively. Some options include coffee houses, the library, or even a quiet, outdoor location when the weather is fine. Look at a variety of places instead of stopping at the first place you like.

- Bring the Necessities and Avoid Distractions– If you only need one book to study from, don’t bring anything to your study session except for that book. That way, there is going to be nothing to distract you. Turn off your cell phone, and put the games away until you have finished studying. Only bring to your study sessions what you absolutely need. If you don’t need your laptop, leave it in your dorm room. In many cases, as long as you have taken notes all semester, all you will need is your notes, the textbook, and a pencil to take more notes.

- Take Breaks and Reward Yourself– You can’t study for hours on end without taking breaks. You need to get up and move around, get something to eat, etc. You also need to reward yourself for a job well done. For instance, if you have studied for a certain period of time, order yourself a pizza as a reward or treat. If you ace that exam, go out and buy yourself something new. This positive reinforcement will make studying even easier in the future.

Byline:

Jane Hurst has been working in education for over 5 years as a teacher. She loves sharing her knowledge with students, is fascinated about edtech and loves reading, a lot. Follow Jane on Twitter!

Thank you!

College Grade Inflation Goes Higher And Higher

Since the last significant release of the survey, faculty members at Princeton University and Wellesley College, among other institutions, have debated ways to limit grade inflation, despite criticism from some students who welcome the high averages. But the new study says these efforts have not been typical. The new data, by Stuart Rojstaczer, a former Duke University professor, and Christopher Healy, a Furman University professor, will appear today on the websiteGradeInflation.com, which will also have data for some of the individual colleges participating in the study.

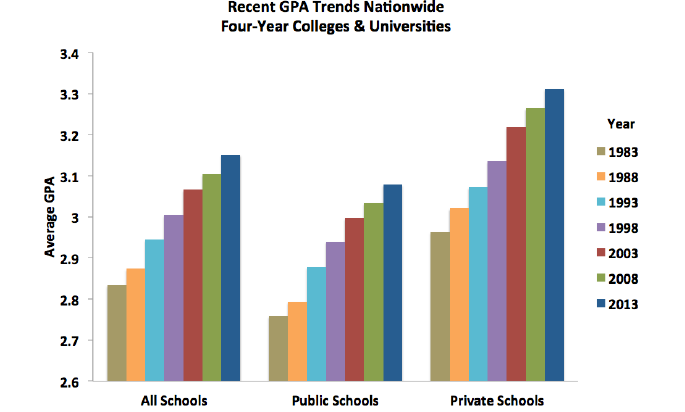

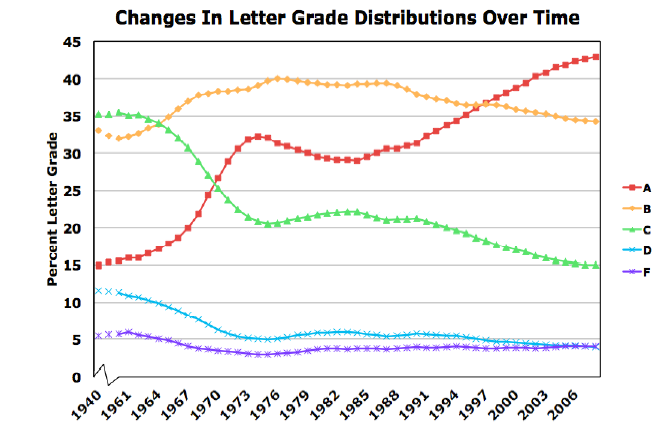

The findings are based on an analysis of colleges that collectively enroll about one million students, with a wide range of competitiveness in admissions represented among the institutions. Key findings:

- Grade point averages at four-year colleges are rising at the rate of 0.1 points per decade and have been doing so for 30 years.

- A is by far the most common grade on both four-year and two-year college campuses (more than 42 percent of grades). At four-year schools, awarding of A’s has been going up five to six percentage points per decade and A’s are now three times more common than they were in 1960.

- In recent years, the percentage of D and F grades at four-year colleges has been stable, and the increase in the percentage of A grades is associated with fewer B and C grades.

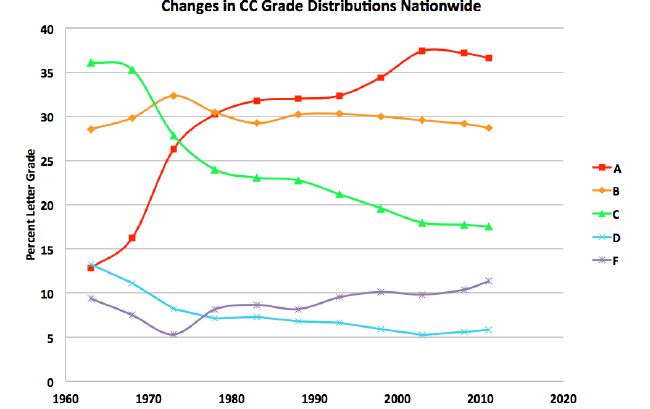

- Community college grades appear to have peaked.

- At community colleges, recent years have seen slight increases in the percentages of D and F grades awarded. While A is still the top grade (more than 36 percent), its share has gone down slightly in recent years.

Here are some of the graphics being released today, appearing here via permission of GradeInflation.com, which show the various trends for grade point averages at four-year colleges and universities, grade distribution at four-year colleges and universities, and grade distributions at community colleges:

The trends highlighted in the new study do not represent dramatic shifts but are continuation of trends that Rojstaczer and many others bemoan.

He believes the idea of “student as consumer” has encouraged colleges to accept high grades and to effectively encourage faculty members to award high grades.

“University leadership nationwide promoted the student-as-consumer idea,” he said. “It’s been a disastrous change. We need leaders who have a backbone and put education first.”

Rojstaczer said he thinks the only real solution is for a public federal database to release information — for all colleges — similar to what he has been doing with a representative sample, but still a minority of all colleges. “Right now most universities and colleges are hiding their grades. They’re too embarrassed to show them,” he said. “As they say, sunlight is the best disinfectant.”

Not all scholars of grading and higher education share Rojstaczer’s views, although most agree that grade inflation is real.

A 2013 study published in Educational Researcher, “Is the Sky Falling? Grade Inflation and the Signaling Power of Grades” (abstract available here), argued that a better way to measure grade inflation is to look at the “signaling” power of grades for employment (landing prestigious jobs and higher salaries). To the extent the relationship between earning high grades and doing better after college is unchanged — and that’s what the study found — the “value” of grades can be presumed to have held its ground, not eroded.

Debra Humphreys, senior vice president for academic planning and public engagement at the Association of American Colleges and Universities, said she looks at lots of data to suggest “an underperformance problem,” which raises the question of why grades continue to go up. AAC&U is one of the leaders of the VALUE Project, which aims to have faculty members compare standards for various programs with the goal of common, faculty-driven expectations about learning outcomes. Humphreys said agreement on learning outcomes and assessment is important because so much of what goes on in grading is “so individual.”

“It remains largely a solo act, with no shared program standards for what counts as excellent, good, average or inadequate work,” she said. “So faculty have no firm foundation to stand on when they go against the trend and assign lower grades.”

Community College Students and Faculty Members

In his analysis, Rojstaczer notes that community colleges have some characteristics that might make them as prone to grade inflation as are four-year institutions (and he considers community college grades high, too, even if they aren’t still rising). For example, he notes that many community college leaders embrace the student-as-consumer idea just as do four-year college presidents. And community colleges rely on adjunct instructors, many of whom lack the job security to be confident in being a tough grader, since students tend to favor easier graders in reviews.

Rojstaczer thinks that, to understand grade inflation, one needs to look at the student body at two-year colleges, which he characterizes as less spoiled than those at four-year institutions. “One factor may be that tuition is low at these schools, so students don’t feel quite so entitled,” he writes. “Another factor may be that community college students come, on average, from less wealthy homes, so students don’t feel quite so entitled.”

Thomas Bailey, George and Abby O’Neill Professor of Economics and Education and director of the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University, agreed via email that he also thinks tuition and student expectations may play a role.

“I would imagine that four-year colleges are more likely to compete on the basis of grades than community colleges,” he said. “Most community college students go to the closest college, so they don’t shop around as much, so there would be less chance that they would benefit from a reputation of high grades. In terms of the notion of entitlement, it might be that students who pay more would feel more willing to demand some sort of accommodation. I believe that among four-year colleges, grade inflation is higher for privates, who charge more, than it is for publics.”

Student Cheating On Line: How Prevalant?

By Danika McLure

It’s hardly breaking news that students cheat in school. From peeking at their peers’ answers on quizzes, to downloading essays from the internet, educators have dealt with academic dishonesty for as long as education has existed.

Students have been documented cheating on quizzes, projects, homework, and even the SAT, so much so, in fact, that non-students have been banned from taking it. Even in the most prestigious institutions, students have proven themselves untrustworthy.

Surveys of Harvard University’s freshmen population revealed that ten percent of students had cheated on exams, and 17 percent admitted to cheating on a paper or take-home assignment. Even more shocking was the amount of students who admitted to cheating on a homework assignment or problem set–42 percent.

Information compiled by the University of Illinois-Chicago confirms these findings, noting that between 35 and 40 percent of uncited material is copied either from a printed or internet based source.

Naturally, findings like these have caused professors to examine ways to prevent cheating in the student population. And with the prevalence of online learning environments, professors are wondering how to tackle plagiarism and cheating in an online environment. Is online testing fair? Does an online learning environment foster dishonesty more so than a traditional classroom does?

These are fair question, especially when you consider that over 6.4 million students are currently enrolled in online learning environments.

Certainly there are hurdles to be overcome in an online classroom. Unlike traditional classrooms, where student exams are easily proctored by professors or student aids, there’s a fear that online students may be able to open alternate browsers, use their mobile devices, or work together alongside their peers. Beyond that, there are a vast number of entrepreneurs and freelancers who advertise services designed to help students cheat in their online courses–all for the completely reasonable price of $1200 for a guaranteed “B”.

Boston University Professor Jay Halfond, alongside his colleague Dennis Berkey recently conducted surveys of online professors, questioning the prevalence of cheating and dishonesty in distance learning, as well as ways they might go about addressing the issue.

As he notes in a column on The Huffington Post, out of the 141 respondents, 80 percent agreed that student dishonesty was an issue throughout American higher education. Surprisingly, nearly the same number of professors reported that they, “as stewards of their online programs,” had cheating under control–largely through outsourcing.

Halfond notes that the ed-tech industry has experienced tremendous growth over the past few years, now attracting a $1.61 million investment annually. As such, engineers have recognized the profitability of creating software which helps professors maintain academic integrity in the classroom. Software has been developed which helps evaluate originality in writing, gauging authentic student participation, and high tech software which has facial recognition.

In fact, for as often as cheating is considered a universal, natural tendency for college students to partake in, new research suggests that for online students–whose potential for dishonest behavior appears to be abundant–there is little evidence of cheating.

On March 29, a digital exam proctoring company called Examity released findings from tests it helped proctor last fall. In reviewing the 62,534 final exams, the company found that a mere six percent of students (3,952) broke test rules–a far cry from numbers e-learning opponents might suggest occurs.

Although it’s entirely possible that the company may have only been able to detect a fraction of the cheating occurred–Quartz reports that they managed to catch a variety of “gutsy endeavors” put forth by students, including an instance where “a mom hid underneath the desk of the test-taker to communicate answers,” as well as an instance in which a “test-taker faked a coughing fit to extricate a cheat sheet in the back of his throat.” Examples which suggest the company investigated the student exams quite thoroughly.

What may be a more important consideration when it comes to online learning, is noting that desperate students might also go to great lengths to cheat. With technological advancements curbing the tendency for students to cheat in online courses, professors are able to focus more on engaging students, rather than policing their behavior.

Danika McClure is a writer and musician from the northwest who sometimes takes a 30 minute break from feminism to enjoy a tv show. You can follow her on twitter @sadwhitegrrl

Are Colleges Too Obsessed With Smartness And Neglect Students?

BY Eric Hoover

Alexander W. Astin has something to say — a lot to say, really — about smartness. He knows some people won’t want to hear it, especially if they happen to teach college students for a living.

Mr. Astin, a professor emeritus at the University of California at Los Angeles, believes that too many faculty members “have come to value merely being smart more than developing smartness.” That line comes from his new book, Are You Smart Enough? How Colleges’ Obsession With Smartness Shortchanges Students.

In the short yet provocative text, Mr. Astin peers into the faculty lounge as well as the admissions office. There he finds more concern with “acquiring” smart students, as defined by conventional metrics, than with helping students improve after they enroll.

“When the entire system of higher education gives favored status to the smartest students, even average students are denied equal opportunities,” he writes. “If colleges were instead to be judged on what they added to each student’s talents and capacities, then applicants at every level of academic preparation might be equally valued.”

Mr. Astin, founding director of UCLA’s Higher Education Research Institute, has written extensively about these issues before. In an interview with The Chronicle on Wednesday, he discussed his new book. Following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

Q. What’s your sense of the prevailing definition of smartness at selective colleges, and what’s so wrong with it?

A. Because of the culture they find themselves immersed in, faculty members tend to be preoccupied with smartness. It’s largely unconscious, I think. We’re often trying to show off our smartness to each other, or avoid being judged as not smart enough. The problem is the consequence of that emphasis.

We concentrate far too much on our smartest students. Smartest in the traditional sense, kids who get the highest grades and test scores. We put tremendous emphasis on these students to the detriment of everybody else — the average student, the underprepared student.

We have created an institutional structure that reflects this bias. Teaching an average student doesn’t get any value in academia. And a side effect of all this is we define smartness in a very narrow sense.

Q. In the book you describe a belief system, or “folklore,” that underpins our understanding of which colleges are best, which students are smartest. How did this evolve?

A. I use the term “folklore” because it’s something that’s passed along by word of mouth, from generation to generation, from person to person, and it isn’t necessarily true or valid. It’s the belief that, Wow, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and so forth — these are the best colleges. Their names conjure up quality. There are certain qualities you can ascribe to these elite institutions, like their huge endowments, their selective admissions processes. And our belief system is that they’re the best because the smartest kids choose them.

Q. And we think of those students as “the smartest” because of measures that you just described as narrow. You have some gripes about standardized tests.

A. I’m a psychologist, trained in statistics. The people who make these tests are like me, kind of mesmerized by the normal curve and the elegance of the stats that underlie the normal curve. We unthinkingly come up with scores that inevitably rank students. But there’s not much information in an ACT or SAT score. Students don’t repeat those tests in college. This adds up to a practice that prevents our system from realizing its potential to benefit society.

Q. Specifically, you believe this notion of smartness relates to questions about equity, such as how to provide more opportunities to underrepresented-minority groups and those from low-income backgrounds.

A. These very narrow measures of standardized tests and grades, when they’re used competitively to sort and select rather than to educate well our students, they put large segments of society at a tremendous competitive disadvantage.

Q. To be fair, admissions officers would say they take these disadvantages into account on a case-by-case basis. Even though they also rely on quantitative assessments to preserve the efficiency of an admissions process deluged with tons of applicants.

A. The fact is, virtually every private college pre-screens applicants based on their test scores. So they might talk about how they value creativity and all these things —

Q. “Your application will be reviewed holistically only after you’ve passed through this quantitative hoop …”

A. You got it. We’re wedded to this test-score mentality. We think we have to have a number we can refer to when picking people. There’s a cost associated with that. The people who get screwed over are the ones who don’t have high-enough numbers, which is why I think the admissions process should be more qualitative than it is now.

I recall a medical-school applicant [at UCLA] who had awful test scores, but the student had created a charitable organization and run it for years in a big city. That takes originality, entrepreneurship, and leadership.

Q. What about your own experience as an educator? Did your views of your obligations to help less-prepared students evolve over time?

A. My experience with underprepared students has been primarily with the doctoral students I teach. We’ve admitted a lot of underprepared doctoral students, consciously. The challenge of helping those students get up to snuff was incredible. That experience has helped shape some of my viewpoints about this. There were a couple of students we didn’t succeed with. The majority of them did succeed.

Q. In the book you describe research on different aspects of smartness, various facets of intelligence. What have you seen that tells you students can be “smart” in very different ways?

A. In the domains of creativity, especially artistic creativity, there’s very little overlap with traditional smartness. Leadership is another fascinating area. So many college mission statements talk about leadership, and it has very little relationship to SAT smartness. Then there’s what we might call character — honesty, trustworthiness, authenticity.

Q. What would you say to faculty members who really do care about those qualities, or who might share some of the concerns about the academic culture that you’ve raised in your book?

A. The first challenge is to become more conscious of the culture, of how the focus on smartness has kind of overwhelmed us in some ways. They might say, “Astin is full of it,” and, you know, that’s a good start, because there will be people who will agree with some of what I’m saying.

Q. OK, so I have this daydream that one day a big-name university shocks the world by announcing that it plans to fill half of its first-year class with students who have mediocre grades and test scores, but who show promise in some other way. In a kind of grand social experiment, this super-prestigious university would essentially set out to prove that its faculty really is as great as it’s cracked up to be, so great that it can take less-than-spectacular students and make them better. Does that strike you as cuckoo?

A. It’s a grand idea. If you’re going to experiment like this, it would be a lot easier for an elite institution to do it. Today, the fact is, most of the wonderful outcomes at elite institutions are a result of the inputs.

Eric Hoover writes about admissions trends, enrollment-management challenges, and the meaning of Animal House, among other issues. He’s on Twitter @erichoov, and his email address is eric.hoover@chronicle.com.